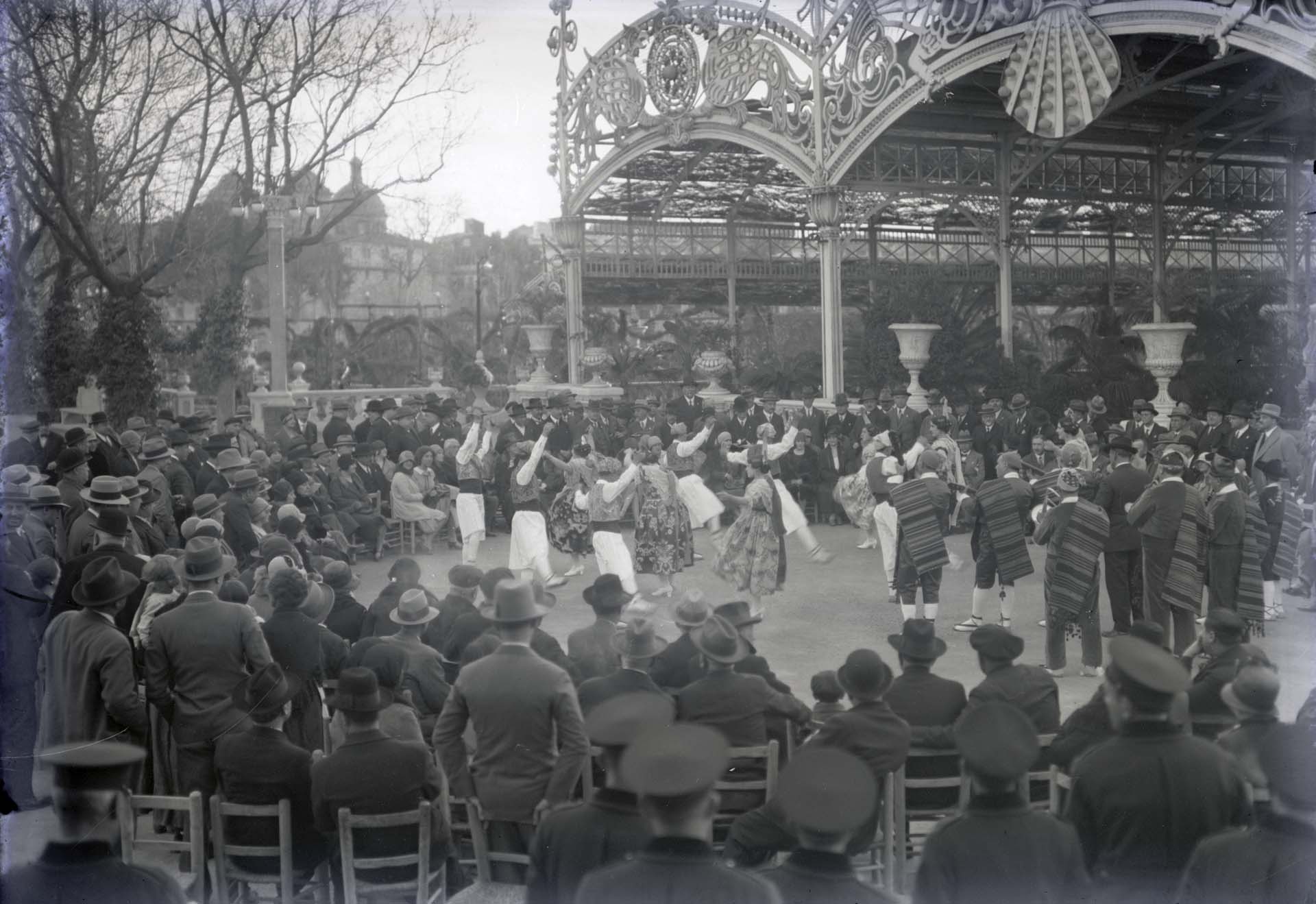

Understanding the Fallas of València

Discover, in this summarized version, the history of the Fallas and its significance for the people of Valencia. There’s nothing better to enjoy a festival than to understand its roots!

Keep planning your visit to Fallas of València

Accommodation options during Fallas

Discover the best places to stay during Fallas in Valencia. From hotels to apartments, find your perfect accommodation for an unforgettable experience.

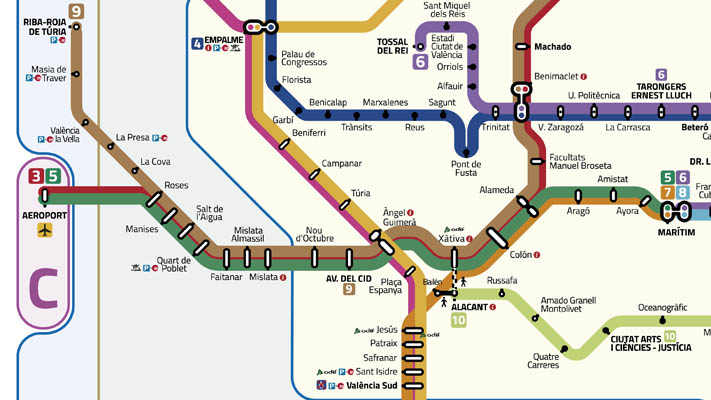

Getting around València during Fallas

Navigate Valencia during Fallas with ease. Learn about transportation options, routes, and tips to move around the city efficiently during the festival.

Valencia Transport System

Explore Valencia’s efficient transport system. Learn about buses, metro, and other transportation modes to navigate the city during Fallas and beyond.

How to get to Valencia during Fallas

Plan your journey to Valencia for Fallas festival. Explore transportation options, routes, and essential tips for traveling to Valencia during this vibrant celebration.

Parking during Fallas in Valencia

Find parking solutions for Fallas in Valencia. Discover the best parking options, tips, and insights to ensure a smooth experience during the festival.

Tips for traveling to Valencia during Fallas

Prepare for your trip to Valencia during Fallas festival. Get valuable tips on safety, cultural norms, and insider advice to make the most of your visit.